William Jackson Hooker on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

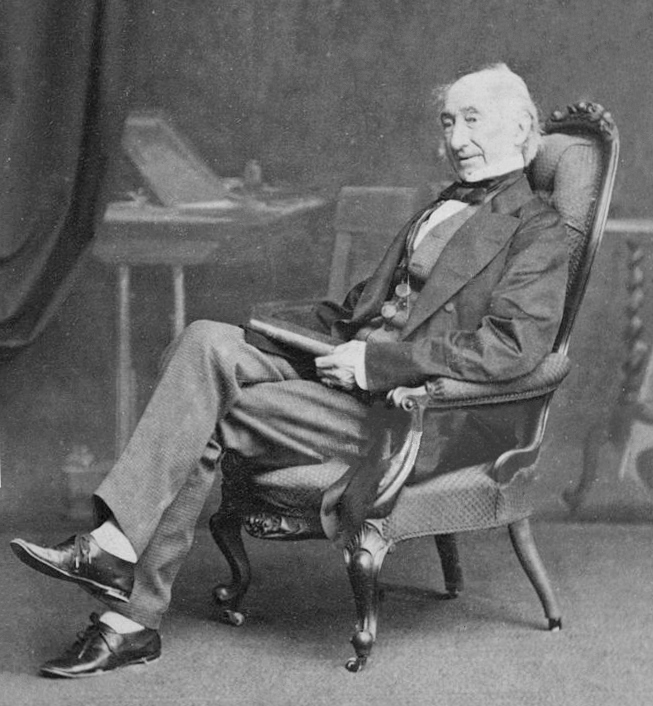

Sir William Jackson Hooker (6 July 178512 August 1865) was an English

Hooker inherited enough money to be able to travel at his own expense. His first botanical expedition abroad—at the suggestion of the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who had made a previous visit in 1772—was to

Hooker inherited enough money to be able to travel at his own expense. His first botanical expedition abroad—at the suggestion of the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who had made a previous visit in 1772—was to

In February 1820, Hooker was appointed as the regius professor of

In February 1820, Hooker was appointed as the regius professor of

Colegate's Guide to Dunoon, Kirn, and Hunter's Quay'' (Second edition)

– John Colegate (1868), page 35 "He seems to have devoted special attention to the vegetation of the neighbourhood," wrote John Colegate in 1868. "The result of his inquiries were published in the Rev. Dr. McKay's ''Statistical Account of the United Parishes of Dunoon and Kilmun''."

In June 1815 he married Maria Sarah Turner,William Jackson Hooker in "England, Norfolk, Parish Registers (County Record Office), 1510–1997 ''FamilySearch''

In June 1815 he married Maria Sarah Turner,William Jackson Hooker in "England, Norfolk, Parish Registers (County Record Office), 1510–1997 ''FamilySearch''

William Jackson Hooker

. the eldest daughter of Dawson Turner and Mary Palgrave. Maria was an amateur artist who collected mosses, and who with her sister Elizabeth illustrated them for her husband. The couple toured

File:The paradisus londinensis (8317590251).jpg, alt=illustration of flower species , '' Bromelia aquilegia'', from ''

Details of the books, articles, etc. written by William Jackson Hooker

from the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Details of collections in the United Kingdom containing Hooker's correspondence, notes and drawings

from

The Hookers' blue plaque

at Kew (

botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

and botanical illustrator, who became the first director of Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is a ...

when in 1841 it was recommended to be placed under state ownership as a botanic garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

. At Kew he founded the Herbarium and enlarged the gardens and arboretum.

Hooker was born and educated in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

. An inheritance gave him the means to travel and to devote himself to the study of natural history, particularly botany. He published his account of an expedition to Iceland in 1809, even though his notes and specimens were destroyed during his voyage home. He married Maria, the eldest daughter of the Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

banker Dawson Turner

Dawson Turner (18 October 1775 – 21 June 1858) was an English banker, botanist and antiquary. He specialized in the botany of cryptogams and was the father-in-law of the botanist William Jackson Hooker.

Life

Turner was the son of Jam ...

, in 1815, afterwards living in Halesworth

Halesworth is a market town, civil parish and electoral ward in north-eastern Suffolk, England. The population stood at 4,726 in the 2011 Census. It lies south-west of Lowestoft, on a tributary of the River Blyth, upstream from Southwold. T ...

for 11 years, where he established a herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (called ...

that became renowned by botanists at the time.

He held the post of Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow University

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, where he worked with the botanist and lithographer

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

Thomas Hopkirk

Thomas Hopkirk (1785–1841) was a Scottish botanist and lithographer.

The Hopkirks

He was descended from a gentry family who came from Hopekirk, near Hawick, by way of Dalkeith in Midlothian, to Dalbeth in Glasgow . His grandfather, also Thom ...

and enjoyed the supportive friendship of Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

for his exploring, collecting and organising work. in 1841 he succeeded William Townsend Aiton as Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,10 ...

. He expanded the gardens at Kew, building new glasshouses, and establishing an arboretum and a museum of economic botany. Among his publications are ''The British Jungermanniae'' (1816), ''Flora Scotica'' (1821), and ''Species Filicum'' (184664).

He died in 1865 from complications due to a throat infection, and was buried at St Anne's Church, Kew

St Anne's Church, Kew, is a parish church in Kew in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. The building, which dates from 1714, and is Grade II* listed, forms the central focus of Kew Green. The raised churchyard, which is on three side ...

. His son, Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

, succeeded him as Director of Kew Gardens.

Family

Hooker's father Joseph Hooker was related to theBaring family

The Baring family is a Germans, German and British people, British family of merchants and bankers. In Germany, the family belongs to the ''Bildungsbürgertum'', and in England, it belongs to the Aristocracy (class), aristocracy.

History

The fa ...

and worked for them in Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

and Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

as a wool-stapler

A wool-stapler is a dealer in wool. The wool-stapler buys wool from the producer, sorts and grades it, and sells it on to manufacturers.

Some wool-staplers acquired significant wealth, such as Richard Chandler of Gloucester (England) who built W ...

, trading in worsted

Worsted ( or ) is a high-quality type of wool yarn, the fabric made from this yarn, and a yarn weight category. The name derives from Worstead, a village in the English county of Norfolk. That village, together with North Walsham and Aylsham, for ...

and bombazine

Bombazine, or bombasine, is a fabric originally made of silk or silk and wool, and now also made of cotton and wool or of wool alone. Quality bombazine is made with a silk warp and a worsted weft. It is twilled or corded and used for dress- ...

. He was an amateur botanist who collected succulent plant

In botany, succulent plants, also known as succulents, are plants with parts that are thickened, fleshy, and engorged, usually to retain water in arid climates or soil conditions. The word ''succulent'' comes from the Latin word ''sucus'', meani ...

s, and was, according to his grandson Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of ...

, "mainly a self-educated man and a fair German scholar". Joseph Hooker was related to the sixteenth-century historian John Hooker John Hooker may refer to:

*John Hooker (English constitutionalist) (c. 1527–1601), English writer, solicitor, antiquary, civic administrator and advocate of republican government

*John Lee Hooker (1912–2001), American blues singer-songwriter an ...

, and the theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

Richard Hooker

Richard Hooker (25 March 1554 – 2 November 1600) was an English priest in the Church of England and an influential theologian.The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church by F. L. Cross (Editor), E. A. Livingstone (Editor) Oxford University ...

.

His mother Lydia Vincent, the daughter of James Vincent, belonged to a family of Norwich worsted weavers and artists. Her cousin William Jackson was William Jackson Hooker's godfather. Upon his death in 1789 William Jackson bequeathed his estate in Seasalter

Seasalter is a village (and district council ward) in the Canterbury District of Kent, England. Seasalter is on the north coast of Kent, between the towns of Whitstable and Faversham, facing the Isle of Sheppey across the estuary of the River Swa ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, to his godson, who inherited it when he was 21. Lydia Vincent's nephew George Vincent was one of the most talented of the Norwich School of painters

The Norwich School of painters was the first provincial art movement established in Britain, active in the early 19th century. Artists of the school were inspired by the natural environment of the Norfolk landscape and owed some influence to the wo ...

.

Biography

Early life and education

William Jackson Hooker was born on 6 July 1785 at 7177 Magdalen Street, Norwich. A child named William Jacson Hooker was christened by his parents Joseph and Lydia Hooker at thenonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

Tabernacle in Norwich on 9 November 1785. He attended the Norwich Grammar School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

from about 1792 until his late teens, but none of the school records from the period he was there have been kept, and little is known of his schooldays. He developed an interest in entomology

Entomology () is the science, scientific study of insects, a branch of zoology. In the past the term "insect" was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such ...

, reading and natural history during his boyhood.

In 1805, Hooker discovered a moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

(now known as '' Buxbaumia aphylla'') when out walking on Rackheath, north of Norwich. He visited the Norwich botanist Sir James Edward Smith James Edward Smith may refer to:

* James Edward Smith (botanist), English botanist and founder of the Linnean Society

* James Edward Smith (murderer), American murderer

* James Edward Smith (politician), Canadian businessman and mayor of Toronto

* ...

to consult his Linnean collections. Smith advised the young Hooker to contact the botanist Dawson Turner

Dawson Turner (18 October 1775 – 21 June 1858) was an English banker, botanist and antiquary. He specialized in the botany of cryptogams and was the father-in-law of the botanist William Jackson Hooker.

Life

Turner was the son of Jam ...

about his discovery.

Upon reaching the age of 21 he inherited an estate in Kent from his godfather. His independent means allowed him to travel and develop his interest in natural history.

As a young man Hooker was fascinated by the endemic birds of Norfolk and spent time studying them on the Broads

The Broads (known for marketing purposes as The Broads National Park) is a network of mostly navigable rivers and lakes in the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. Although the terms "Norfolk Broads" and "Suffolk Broads" are correctly use ...

and the Norfolk coast. He became skilled in drawing them and understanding their behaviour. He also studied insects and, when still at school, his skills were appreciated by the Reverend William Kirby. In 1805, Kirby dedicated the '' Omphalapion hookerorum'', a species of weevil

Weevils are beetles belonging to the superfamily Curculionoidea, known for their elongated snouts. They are usually small, less than in length, and herbivorous. Approximately 97,000 species of weevils are known. They belong to several families, ...

, to him and his brother Joseph: "I am indebted to an excellent naturalist, Mr. W. J. Hooker, of Norwich, who first discovered it, for this species. Many other nondescripts have been taken by him and his brother, Mr. J. Hooker, and I name this insect after them, as a memorial of my sense of their ability and exertions in the service of my favourite department of natural history."

In 1805 Hooker went to be trained in estate management at Starston Hall, Norfolk, perhaps because of the need to be able to manage his own newly acquired estates. He lived there with Robert Paul, a gentleman farmer

In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, a gentleman farmer is a landowner who has a farm (gentleman's farm) as part of his estate and who farms mainly for pleasure rather than for profit or sustenance.

The Collins English Diction ...

. In 1806 he was introduced to Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

, the president of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. He elected to the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature colle ...

that year.

Early friends and patrons

When a young man, Hooker gained the patronage and friendship of some of most important naturalists in eastern England, including Smith, who had founded the Linnean Society of London in 1788 and ownedCarl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

's collection of plants and books, the botanist and antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

Dawson Turner, and Joseph Banks.

In 1807, Hooker was bitten by an adder when walking near Burgh Castle

Burgh Castle is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the east bank of the River Waveney, some west of Great Yarmouth and within the Norfolk Broads National Park. The parish was part of Suffolk until ...

and badly hurt. He was found by friends and taken to Dawson Turner's house, where he was cared for until he recovered completely from the effects of the snake's bite. Once he had fully recovered, he accompanied Turner and his wife Mary on a tour of Scotland. In 1808 he again travelled to Scotland, this time accompanied by his friend William Borrer

William Borrer ( Henfield, Sussex, 13 June 1781 – 10 January 1862) was an English botanist noted for his extensive and accurate knowledge of the plants of the British Islands.

He travelled extensively around Britain to see and collect plan ...

. During this journey he discovered a new species of moss, '' Andreaea nivalis'', on Ben Nevis

Ben Nevis ( ; gd, Beinn Nibheis ) is the highest mountain in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland ...

, which may have led to him publishing a paper ''Some Observations on the Genus Andreaea'' in 1810.

Hooker produced the illustrations for James Edward Smith's paper ''Characters of ''Hookeria

''Hookeria'' is a genus of mainly tropical mosses. It was defined by James Edward Smith James Edward Smith may refer to:

* James Edward Smith (botanist), English botanist and founder of the Linnean Society

* James Edward Smith (murderer), America ...

'', a new Genus of Mosses, with Descriptions of Ten Species'', a genus named by Smith in honour of William and his older brother Joseph. Hooker had discovered a specimen of the moss in the countryside around Holt. From 1806 to 1809 he was a constant guest of Dawson Turner in Yarmouth, where he produced the illustrations for Turner's four-volume ''Historia Fucorum''. He also spent time in London, where he took up rooms in Frith Street

Frith Street is in the Soho area of London. To the north is Soho Square and to the south is Shaftesbury Avenue. The street crosses Old Compton Street, Bateman Street and Romilly Street.

History

Frith Street was laid out in the late 1670s an ...

, near the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

By 1807 Hooker had begun work as a supervising manager at a brewery

A brewery or brewing company is a business that makes and sells beer. The place at which beer is commercially made is either called a brewery or a beerhouse, where distinct sets of brewing equipment are called plant. The commercial brewing of bee ...

at Halesworth

Halesworth is a market town, civil parish and electoral ward in north-eastern Suffolk, England. The population stood at 4,726 in the 2011 Census. It lies south-west of Lowestoft, on a tributary of the River Blyth, upstream from Southwold. T ...

, in partnership with Dawson Turner and Samuel Paget. Sharing a quarter of the company, he lived in the brewery house, which had a large garden and a greenhouse in which he grew orchids

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowering ...

. The brewing venture proved to be unsuccessful, for he had no capacity for business. He remained as the manager there for ten years, living at 15 Quay Street, Halesworth.

Excursions abroad

Hooker inherited enough money to be able to travel at his own expense. His first botanical expedition abroad—at the suggestion of the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who had made a previous visit in 1772—was to

Hooker inherited enough money to be able to travel at his own expense. His first botanical expedition abroad—at the suggestion of the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who had made a previous visit in 1772—was to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, in the summer of 1809. He sailed on the ''Margaret and Anne'', arriving at Reykjavík

Reykjavík ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland, on the southern shore of Faxaflói bay. Its latitude is 64°08' N, making it the world's northernmost capital of a sovereign state. With a po ...

in June. That month an attempt at Icelandic independence was staged by the Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen

Jørgen Jørgensen (name of birth: Jürgensen, and changed to Jorgenson from 1817)Wilde, W H, ''Oxford Companion to Australian Literature'' 2nd ed. (29 March 1780 – 20 January 1841) was a Danish adventurer during the Age of Revolution. Dur ...

. Two months later, HMS Talbot anchored in Reykjavík harbour and her commander promptly deposed and arrested Jorgensen, and restored the governor.

During his return voyage, the ''Margaret and Anne'', in a dead calm, was discovered to be on fire, the result of sabotage which was afterwards found to have been planned by Danish prisoners. Hooker and the ship's company were all rescued, but the fire destroyed most of his drawings and notes. Banks later offered Hooker the use of his own papers, and with these materials, along with the surviving parts of his own journal, his good memory aided him to publish an account of the island, its inhabitants and flora: his ''A Journal of a Tour in Iceland (1809)'' was privately circulated in 1811 and published two years later.

In 1810–11 he made extensive preparations, and sacrifices which proved financially serious, with a view to travelling to Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, to accompany the newly-appointed governor, Sir Robert Brownrigg

General Sir Robert Brownrigg, 1st Baronet, GCB (8 February 1758 – 27 April 1833) was an Irish-born British statesman and soldier. He brought the last part of Sri Lanka under British rule.

Early career

Brownrigg was commissioned as an e ...

. He sold property inherited from his godfather, William Jackson, to raise the necessary capital for the journey. Political upheaval there led to the project being abandoned. In 1812 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

In 1813, encouraged by Sir Joseph Banks, he considered travelling to Java, but was dissuaded from the idea by friends and family.

In 1814 he travelled in Europe for nine months, going to Paris with the Turners, then travelling alone to Switzerland, southern France, and Italy, where he studied plants and visited notable botanists. The following year he married the eldest daughter of his friend Dawson Turner. Settling at Halesworth, he devoted himself to the formation of his herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (called ...

, which became of worldwide renown among botanists. In 1815, he was made a corresponding member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Career in Glasgow

In February 1820, Hooker was appointed as the regius professor of

In February 1820, Hooker was appointed as the regius professor of botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

in the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, taking over from the Scottish physician and botanist Robert Graham, and inheriting a small botanic garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

that was underfunded and lacking in plants. In May he was received by the University and read his inaugural thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, written by his father-in-law, Dawson Turner. Hooker was faced with the prospect of delivering lectures to students, when he had never previously taught, and was ignorant of some aspects of botany: his position within the medical faculty inspired him to study for a medical degree.

He soon became popular as a lecturer, his style being both clear and eloquent, and people such as local army officers came to attend them. For 15 years he delivered a summer course on botany, required to be studied by all medical students—for the remaining months of the year he was free to study, work on his publications and his herbarium, and correspond with other botanists. His classroom was remarkable for having drawings of plants on display to assist the students, and their course included trips to study plants, organised by Hooker. Student numbers increased from 30 in 1820 to 130 ten years later. He earned £144 in his first year, which later increased, but still needed to supplement his income by tutoring two boys from wealthy families, who lived with the family.

His years at Glasgow were his most productive, when he was known as the most active botanist in the country. In 1821 he brought out the '' Flora Scotica'', written to be used by his botany students. He was awarded a doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

by Glasgow University in 1821. He worked with the lithographer

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

and botanist Thomas Hopkirk

Thomas Hopkirk (1785–1841) was a Scottish botanist and lithographer.

The Hopkirks

He was descended from a gentry family who came from Hopekirk, near Hawick, by way of Dalkeith in Midlothian, to Dalbeth in Glasgow . His grandfather, also Thom ...

to establish the Royal Botanic Institution of Glasgow and to lay out and develop the Botanic Gardens. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1823.

Under Hooker, the Botanic Gardens enjoyed remarkable success and became prominent in the botanic world. The garden was his responsibility and he set to work developing it with the help of his extensive network of friends and acquaintances. Principal among these was Sir Joseph Banks, who promised Kew's help. The botanic gardens steadily acquired new plants, often from visiting naturalists, or from students who had travelled. His work on the botanic garden resulted in experts expressing the view that "Glasgow would not suffer by comparison with any other establishment in Europe".

During his professorship at Glasgow, his numerous published works included ''Flora Londinensis'', ''British Flora'', ''Flora Boreali-Americana'', ''Icones Filicum'', ''The Botany of Captain Beechey's Voyage to the Bering Sea'', ''Icones Plantarum'', ''Exotic Flora'' (1823–27), 13 volumes of ''Curtis's Botanical Magazine'' (from 1827), and the first seven volumes of ''Annals of Botany''.

In 1836 Hooker was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order and a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in recognition of his work at Glasgow and his services to botany. Although officially recognised in this way, he became increasingly disillusioned with how his work was viewed by the University authorities, and by 1839 was feeling as if the "dignity of the position was stripped to one of ridicule and his work was dismissed as of no account".

During his time in Glasgow, he lived, for several summers, at Invereck at the head of the Holy Loch

The Holy Loch ( gd, An Loch Sianta/Seunta) is a sea loch, a part of the Cowal peninsula coast of the Firth of Clyde, in Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

The "Holy Loch" name is believed to date from the 6th century, when Saint Munn landed there afte ...

.Colegate's Guide to Dunoon, Kirn, and Hunter's Quay'' (Second edition)

– John Colegate (1868), page 35 "He seems to have devoted special attention to the vegetation of the neighbourhood," wrote John Colegate in 1868. "The result of his inquiries were published in the Rev. Dr. McKay's ''Statistical Account of the United Parishes of Dunoon and Kilmun''."

Director of Kew Gardens

The origins of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew can be traced to the merging of the royal estates ofRichmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and Kew in 1772, when the garden at Kew Park formed by Henry, Lord Capell of Tewkesbury was enlarged by Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales. The gardens were developed by the architect William Chambers, who built the pagoda

A pagoda is an Asian tiered tower with multiple eaves common to Nepal, India, China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most often Buddhist but sometimes Taoist, ...

in 1761, and by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. Both kingdoms were in a personal union under him until the Acts of Union 1800 merged them ...

, who was aided by William Aiton

William Aiton (17312 February 1793) was a Scottish botanist.

Aiton was born near Hamilton. Having been regularly trained to the profession of a gardener, he travelled to London in 1754, and became assistant to Philip Miller, then superinten ...

and Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

. The Dutch House, now known as Kew Palace

Kew Palace is a British royal palace within the grounds of Kew Gardens on the banks of the River Thames. Originally a large complex, few elements of it survive. Dating to 1631 but built atop the undercroft of an earlier building, the main surv ...

, was purchased by George III in 1781 for his children. The adjoining White House was demolished in 1802. The plant collections at Kew were first enlarged systematically by Francis Masson

Francis Masson (August 1741 – 23 December 1805) was a Scottish botanist and gardener, and Kew Gardens’ first plant hunter.

Life

Masson was born in Aberdeen.

In the 1760s, he went to work at Kew Gardens as an under-gardener.

Masson ...

in 1771, but had since the death of George III slowly declined. In 1838, a Parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

review of the nation's royal gardens recommended the development of Kew as a national botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

.

In April 1841 he was appointed as the Garden's first full time Director, on the resignation of William Townsend Aiton

William Townsend Aiton FRHS FLS (2 February 1766 – 9 October 1849) was an English botanist. He was born at Kew on 2 February 1766, the eldest son of William Aiton.

He brought out a second and enlarged edition of the '' Hortus Kewensis'' in 18 ...

. Following his appointment as director, a position he had long wished for, he wrote "I feel as if I were to begin life over again", in a letter to Dawson Turner. He started on an annual salary of £300, with an additional allowance of £200. To Allan, who described Hooker as a man with "drive, enthusiasm and creative ability", he was eminently suited for the post, being a professional botanist, an artist, a leader with connections to others in the botanical world, who was knowledgeable about plants from Britain and those collected from around the world. The curator of Kew Gardens during Hooker's period as Director was the experienced and knowledgeable botanist John Smith (1798–1888).

Under Hooker's direction the gardens expanded considerably in size. Initially about in size, they were extended to in 1841. An arboretum of was introduced, many new glass-houses were erected, and a museum of economic botany was established. In 1843 the Palm House, to a design by the architect Decimus Burton and the iron founder An iron founder (also iron-founder or ironfounder) in its more general sense is a worker in molten ferrous metal, generally working within an iron foundry. However, the term 'iron founder' is usually reserved for the owner or manager of an iron foun ...

Richard Turner, was constructed at Kew. The gardens and glasshouses were opened daily to the visiting public, who were allowed to wander freely there for the first time. Sir William himself wandered around during opening hours, lending his advice.

He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1862.

Hooker lived with his family at West Park, a large house in which he accommodated 13 rooms of books in his library, which was seen as a public institution by the world's botanical experts, who were never turned away. Among his visitors were Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, her husband Prince Albert and their children; during 1865—the year Hooker died—the attendance had risen to 529,241.

Under Hooker's direction Kew became the centre of an emerging interconnected worldwide network of botanical expertise, and staff recommended by him joined expeditions or worked for botanical gardens around the world. He was invariably consulted when government questions arose about botanical matters. Newly propagated plants and sent from Kew to private and public gardens in Britain, and to botanical gardens overseas, in some cases to be developed as crops.

Marriage and family

In June 1815 he married Maria Sarah Turner,William Jackson Hooker in "England, Norfolk, Parish Registers (County Record Office), 1510–1997 ''FamilySearch''

In June 1815 he married Maria Sarah Turner,William Jackson Hooker in "England, Norfolk, Parish Registers (County Record Office), 1510–1997 ''FamilySearch''William Jackson Hooker

. the eldest daughter of Dawson Turner and Mary Palgrave. Maria was an amateur artist who collected mosses, and who with her sister Elizabeth illustrated them for her husband. The couple toured

the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

and across Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

on their honeymoon, before travelling to Scotland.

They had five children. William Dawson Hooker (born 1816) was a naturalist who trained as a doctor. He published ''Notes on Norway'' (1837 and 1839). He emigrated with his new wife to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

to practise medicine, but died at Kingston, aged 24. Joseph Dalton Hooker (born 1817) became a botanist and was appointed the first assistant director at Kew. He served in this post for 10 years, before taking over as director from his father in 1865. The three daughters in the family were Maria (born 1819), Elizabeth (born 1820), and Mary Harriet (born 1825), who died aged sixteen.

Death

He was engaged on the ''Synopsis filicum'' with the botanistJohn Gilbert Baker

John Gilbert Baker (13 January 1834 – 16 August 1920) was an English botanist. His son was the botanist Edmund Gilbert Baker (1864–1949).

Biography

Baker was born in Guisborough in North Yorkshire, the son of John and Mary (née Gilbert ...

when he contracted a throat infection then epidemic at Kew. He died in 1865 and was buried at St. Anne's Church, Kew. He was succeeded at Kew Gardens by his son.

Works

Hooker studied mosses, liverworts, and ferns, and published a monograph on a group of liverworts, ''British Jungermanniae'', in 1816. This was succeeded by a new edition ofWilliam Curtis

William Curtis (11 January 1746 – 7 July 1799) was an English botanist and entomologist, who was born at Alton, Hampshire, site of the Curtis Museum.

Curtis began as an apothecary, before turning his attention to botany and other natural ...

's ''Flora Londinensis

''Flora Londinensis'' is a folio sized book that described the flora found in the London region of the mid 18th century. The ''Flora'' was published by William Curtis in six large volumes. The descriptions of the plants included hand-coloured cop ...

'', for which he wrote the descriptions (18171828); by a description of the ''Plantae cryptogamicae'' of Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

and Aimé Bonpland

Aimé Jacques Alexandre Bonpland (; 22 August 1773 – 11 May 1858) was a French explorer and botanist who traveled with Alexander von Humboldt in Latin America from 1799 to 1804. He co-authored volumes of the scientific results of their ex ...

; by the '' Muscologia'', a very complete account of the mosses of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and Ireland, prepared in conjunction with Thomas Taylor and first published in 1818; and by his ''Musci exotici'' (2 volumes, 18181820), devoted to new foreign mosses and other cryptogamic plants.

Hooker published more than 20 major botanical works over a period of 50 years, including ''British Jungermanniae'' (1816), ''Musci Exotici'' (18181820), ''Icones Filicum'' (18291831), '' Genera Filicum'' (1838) and ''Species Filicum'' (18461864). Other works include ''Flora Scotica'' (1821), ''The British Flora'' (1830) and ''Flora Borealis Americana; or, The Botany of the Northern Parts of British America'' (1840).

Examples

The Paradisus Londinensis

''The Paradisus Londonensis'' (full title ''The Paradisus Londonensis : or Coloured Figures of Plants Cultivated in the Vicinity of the Metropolis'') is a book dated 1805–1808, printed by D.N. Shury, and published by William Hooker.. It consis ...

'' (1805)

File:The paradisus londinensis (8317612271).jpg, alt=illustration of flower species , ''Linum

''Linum'' (flax) is a genus of approximately 200 species''Linum''.

The Jepson Manual.

hypericifilum'' from ''The Paradisus Londinensis'' (1807)

File:William Jackson Hooker - illustration for his paper 'Some Observations on the Genus Andraea'.jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , ''Some Observations on the Genus Andraea'' (1810)

File:Hooker - Jungermannia Spinulosa.jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , '' Jungermannia Spinulosa'', from Hooker's first scientific work, ''British Jungermanniae'' (1816)

File:Curtis's botanical magazine (Plate 3088) (8410403017).jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , '' Xanthochymus dulcis'', from ''The Jepson Manual.

Curtis's Botanical Magazine

''The Botanical Magazine; or Flower-Garden Displayed'', is an illustrated publication which began in 1787. The longest running botanical magazine, it is widely referred to by the subsequent name ''Curtis's Botanical Magazine''.

Each of the issue ...

'' (1831)

File:Flora boreali-Americana, or, The botany of the northern parts of British America (microform) - compiled principally from the plants collected by Dr. Richardson and Mr. Drummond on the late northern (20631052015).jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , '' Valeriana pauciflora'', from ''Flora boreali-Americana'' (1840)

File:The botany of Captain Beechey's voyage; comprising an acount of the plants collected by Messrs. Lay and Collie, and other officers of the expedition, during the voyage to the Pacific and Behring's (19784848113).jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , ''Lewisia rediviva

Bitterroot (''Lewisia rediviva'') is a small perennial herb in the family Montiaceae. Its specific epithet ("revived, reborn") refers to its ability to regenerate from dry and seemingly dead roots.

The genus ''Lewisia'' was moved in 2009 fro ...

'', from ''The Botany of Captain Beechey's Voyage'' (1841)

File:Hooker - Gleichenia acutifolia.jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , '' Gleichenia acutifolia'', from ''Species filium'' (1846)

File:Abrodictyum pluma (Hook - Icones plantarum).jpg, alt=illustration of plant species , '' Abrodictyum pluma'' from ''Icones Plantarum

''Icones Plantarum'' is an extensive series of published volumes of botanical illustration, initiated by Sir William Jackson Hooker. The Latin name of the work means "Illustrations of Plants". The illustrations are drawn from herbarium specimens o ...

'' (1854)

Plants named after Farrer Hooker

A number plants have the Latin specific epithet of ''hookeri'' which refers to Hooker.Allen J. Coombes Including; * '' Allium hookeri'' * '' Alsophila hookeri'' * '' Anthurium hookeri'' * ''Arctostaphylos hookeri

''Arctostaphylos hookeri'' is a species of manzanita known by the common name Hooker's manzanita.

Description

''Arctostaphylos hookeri'' is a low shrub which is variable in appearance and has several subspecies. These are generally mat-forming p ...

''

* ''Dasypogon hookeri

''Dasypogon hookeri'', commonly known as pineapple bush, is a species of shrub in the family Dasypogonaceae

Dasypogonaceae is a family of flowering plants, one that has not been commonly recognized by taxonomists; the plants it contains were ...

''

* '' Drosera hookeri''

* ''Epiphyllum hookeri

''Epiphyllum hookeri'' is a species of climbing cactus in the ''Epiphyllum'' genus. It forms showy white flowers and is native from Mexico through Central America to Venezuela. A perennial, it was introduced to Florida and some West Indies, West ...

''

* '' Iris hookeri''

* '' Kopsiopsis hookeri''

* '' Lithops hookeri''

* '' Lysiphyllum hookeri''

* ''Ozothamnus hookeri

''Ozothamnus hookeri'', commonly known as kerosene bush, is an aromatic shrub species, endemic to Australia. It grows to between 0.5 and 1 metre in height and has white-tomentose branchlets. The scale-like leaves are 4 to 5 mm long and 0.5 ...

''

* '' Notholaena hookeri''

* '' Pachyphytum hookeri''

* ''Prosartes hookeri

''Prosartes hookeri'' is a North American species of flowering plants in the lily family known by the common names drops of gold and Hooker's fairy bells.

Distribution

It is native to western North America from Alberta and British Columbia t ...

''

* '' Pseudarthria hookeri''

* '' Townsendia hookeri''

References

Sources

* * * * *External links

Details of the books, articles, etc. written by William Jackson Hooker

from the Biodiversity Heritage Library

Details of collections in the United Kingdom containing Hooker's correspondence, notes and drawings

from

the National Archives

National archives are central archives maintained by countries. This article contains a list of national archives.

Among its more important tasks are to ensure the accessibility and preservation of the information produced by governments, both ...

The Hookers' blue plaque

at Kew (

English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

)

*

*

* Details of Hooker's will:

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hooker, William Jackson

English botanists

Botanical illustrators

1785 births

1865 deaths

British pteridologists

Botanists with author abbreviations

Botanists active in Kew Gardens

English taxonomists

Economic botanists

Independent scientists

Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Fellows of the Royal Society

Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Academics of the University of Glasgow

Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

People educated at Norwich School

People from Halesworth

Writers from Norwich

Burials at St. Anne's Church, Kew

19th-century British botanists

Scientists from Norwich

Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala